Editor’s Note: We are on the cusp of a multi-year oil bull market, and our view is that Latin America offers some of the more compelling energy names in the entire energy sector. This is an old write-up by Jon Costello from July 12, 2024, but it gives you a good overview of Petrobras.

For our latest thoughts on Petrobras, please see today’s article.

By: Jon Costello

Petroleo Brasileiro S.A., or Petrobras (PBR), is Brazil’s national oil and gas company. The company owns and operates exploration and production assets, infrastructure, and 11 refineries. In the first quarter, PBR produced 2.78 million boe/d, split 73%/27% between liquids and natural gas. PBR accounts for 88% of Brazil’s oil and gas production. It also controls 93% of Brazil’s refining capacity. It owns 26 oil tankers, which partially insulates it from the volatility of the global tanker market.

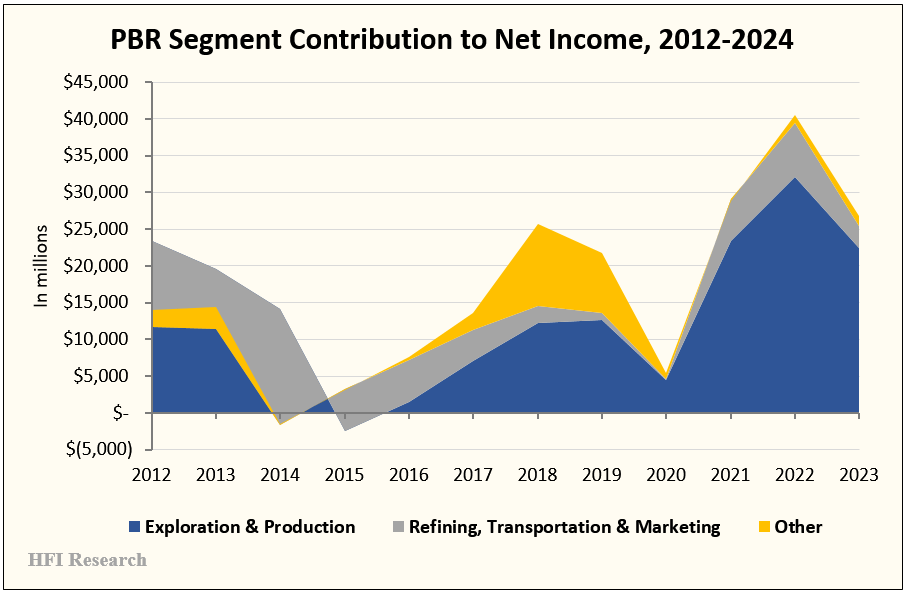

PBR’s economics are relatively straightforward for an operation of its size. PBR’s financial results are dominated by its E&P segment. E&P segment net income typically accounts for 80% to 85% of total corporate net income. Meanwhile, its vertical integration gives it a competitive advantage against domestic refiners.

Analysis becomes more complicated when factoring in the impact of Brazilian politics. The multitude of risks that stem from Brazil’s always fluid political situation call for regular monitoring by PBR investors.

PBR’s U.S. American Depository Receipts for its common shares are listed on the New York Stock Exchange and currently trade at approximately $15. We value the shares in the range of $20 to $25, but a large margin of safety is necessary due to risks pertaining to Brazilian politics and PBR’s long-term production prospects.

For starters, a brief review of PBR’s history helps to grasp the perception versus the reality of risks to the company’s shareholders.

Historical Overview

PBR was founded in 1953 during a global wave of national oil company expropriations. The company was granted a monopoly over Brazil’s exploration, production, refining, and shipping of the country’s crude oil and natural gas. Only the distribution of petroleum products was outside the monopoly’s purview. Upon its formation, PBR was 51% owned by the Brazilian government, while public ownership of its equity was reserved for Brazilian citizens alone.

Unlike other nationalizations in the 1950s—such as those that occurred in Mexico and Iran—Brazil’s establishment of PBR did not involve the seizure of assets from existing private operations. Part of the reason was practical, as Brazil’s domestic oil and gas production was minimal in the early 1950s. Moreover, the Brazilian government already owned existing oil and gas wells, but in 1953, Brazil’s domestic production of 2,500 boe/d represented only 1.5% of its 170,000 boe/d of internal demand, most of which was met through imports.

PBR’s initial assets consisted mostly of a few small refineries. To increase oil and gas production, it would need foreign expertise, so the Brazilian government set it up with a financial structure that attracted risk capital and incentivized exploration.

Over the years, PBR grew irrespective of the Brazilian political regime. By the 1990s, it had matured into a successful, technologically sophisticated company. Its major assets had been built by the company and its partners.

In 1995, as part of a campaign to privatize state-owned industries, the Brazilian government eliminated PBR’s monopoly status. In 1997, Brazil passed its Petroleum Law, which mandated that the Brazilian government would own at least 50% and one share of PBR’s voting capital. The law also established the ANP as PBR’s regulator and allowed the company to retain ownership of its producing fields, as well as its most attractive exploration prospects. Other assets were transferred to the ANP, which allocated Brazil’s exploration blocks to PBR and others.

Despite losing its monopoly status, PBR was able to compete successfully on a global playing field dominated by international majors. In 2006, the company made seminal offshore discoveries that would increase its operating scale and improve its financial performance.

Today, PBR stands as the largest business in Latin America by market cap, with its economic capital mostly in the hands of public investors.

Expropriation Risk is Far Less than Feared

We touch on PBR’s history to differentiate it from its national oil company around the world. Elsewhere in Latin America, for instance, asset expropriations from foreign investors have been common since the 1950s. Recent examples include Venezuela’s expropriations from ConocoPhillips (COP) and ExxonMobil (XOM) under Hugo Chavez and Argentina’s seizure of YPF from Repsol (OTCQX:REPYF). These actions by national governments came with little hesitation even though they clearly violated Constitutional prohibitions on government expropriation of private property. Like other Latin American nations, Brazil has seen its share of regime changes from socialist to capitalist to military dictatorship. However, it has not shown an inclination toward expropriations.

The success of PBR’s capital structure in driving its operational and financial success is one reason why expropriation never made sense. Furthermore, Brazilian government policies successfully supported the nation’s energy investment, infrastructure growth, and consumption since the 1970s. These policies have remained in effect despite the government’s bureaucratic nature and protectionist bent. Through different regimes, they have allowed PBR to operate independently and have made the nation largely energy-independent.

Oil and gas asset expropriations also tend to happen when private owners of a producing entity receive outsized returns relative to the government take. PBR is subject to massive amounts of production taxes and income taxes that it remits to the government. The company’s massive size and world-class assets generate more than enough cash flow to stabilize Brazil’s budget and support its currency while simultaneously generating attractive returns for shareholders to incentivize public ownership and capital market access.

Brazil’s sheer abundance is another factor behind PBR’s success as an independent entity. The nation’s vast size, economic wealth, and resource potential compared to other Latin American nations have allowed PBR to consistently grow its domestic operations by exploiting Brazil’s domestic resources at an increasing scale. Since its growth occurred along with the rapid growth of Brazil’s middle class, the Brazilian government never had the need to change the company’s course.

Political Interference Risk is Over-Hyped

While PBR does not face expropriation risk, it does face constant political risk. The company is subject to political meddling in its top executive ranks and changing tax regimes. Brazil has a long history of endemic corruption in both business and politics, from which PBR isn’t exempt. The most spectacular example was PBR’s “Car Wash” money laundering scandal in 2014, which involved billions of dollars of shareholder losses and ensnared dozens of prominent Brazilian businesspeople and politicians.

Today, Brazil is governed by the leftist Workers Party. The current President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Saliva, or Lula, is not afraid to interfere in PBR’s affairs. As recently as March 8, after he announced a four-month oil export tax that threatens to reduce PBR’s oil exports, Lula pressured PBR’s board of directors to block a $3 billion special dividend the company was set to make to its shareholders. After the dividend was withheld, PBR’s shares traded down 12% that day, just after they had hit a 10-year high fueled by investor optimism regarding PBR’s production growth. Lula’s move caused analysts to worry that the Brazilian government would become more involved in PBR affairs, such as directing spending toward less-profitable renewables projects and social projects.

Then on May 13—in defiance of Lula’s calls for dividend restraint—PBR’s board ended up issuing the special dividend as initially proposed. In response, Lula fired PBR’s CEO. The unexpected move sent the company’s shares down more than 8% that day. As usual after such an event and its associated stock price selloff, analysts voiced their concerns that the CEO’s ouster was aimed at increasing the Worker’s Party’s influence in PBR’s affairs.

Lula nominated Magda Chambriard as the company’s next CEO. Chambriard was part of Lula’s transition team when he returned to power in 2022. She was formerly the head of the ANP, PBR’s regulatory agency. She favors increasing PBR’s downstream investments and steering the company’s future E&P expansion outside of Brazil.

PBR’s share price has been subdued since Chambriard was named CEO in mid-May. Since her appointment, PBR shares have declined by 11%. Their poor performance is primarily attributable to investors’ fear of lower dividend payments.

PBR investors have to be attentive to political interference risk, which will exist as long as the company is controlled by the Brazilian government. As long as it is, PBR’s capital allocation policies will be subject to change on a whim—in a potentially adversely for public shareholders.

Still, political risk to PBR tends to be overstated. For instance, the media chided the company’s incoming management team as being too political when, in fact, the incoming executives have considerable experience and technical expertise. It is clear that they are not mere political appointees. After all, the previous CEO was also a socialist. He was also PBR’s sixth CEO since 2019. The tenure of the current team may also be short, for better or worse.

Other positive indicators pertaining to the Brazilian government’s intentions for PBR include recent financial projections by Treasury Secretary Rogerio Ceron that call for “100% of Petrobras’ extraordinary dividends as the probable scenario.” Brazil’s Planning and Finance Ministry also raised PBR’s annual dividend revenue estimate by $2.78 billion.

Despite the scary headlines, PBR’s plunging stock price, and political wranglings, it appears that the status quo is the most probable case for PBR’s operations, financial performance, and capital allocation.

High-Quality E&P Assets

What PBR has going for it is its world-class portfolio of E&P assets. These assets produce most of PBR’s earnings, so the company’s earning power is largely dependent on their performance. The following chart illustrates their large—and growing—contribution to PBR’s net income since 2012.

Of the company’s E&P assets, deepwater and ultra-deepwater production account for 94% of total oil and gas output. The remaining 6% is produced from mature fields in shallow waters and onshore, as well as from outside Brazil.

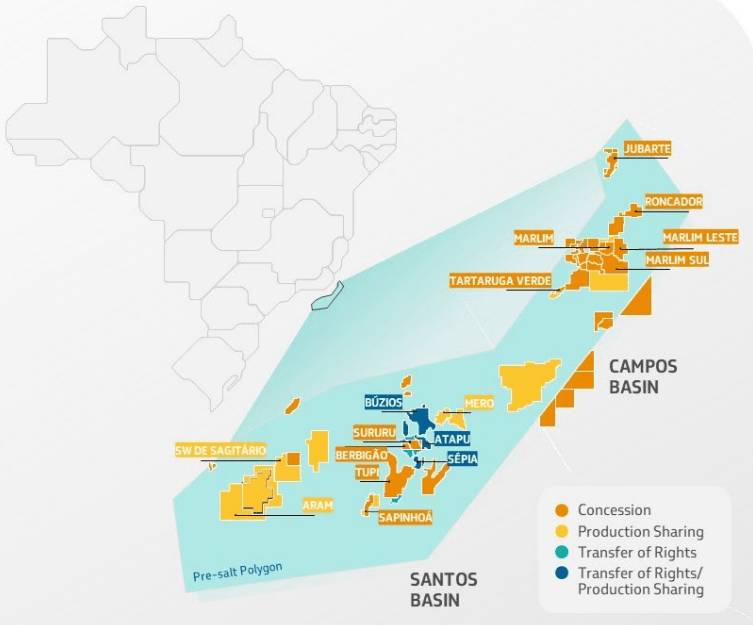

Most of PBR’s production is sourced from the pre-salt fields in the Campos and Santos basins offshore in southeast Brazil. “Pre-salt” refers to thick carbonate reservoirs located under water, rock, and a shifting layer of salt along the continental shelf that extend as much as 25,000 feet below the surface of the Atlantic. Billions of barrels of oil reside in the layer of salt, which is around 6,500 feet thick. PBR operates the pre-salt fields in partnership with other oil majors, including TotalEnergies (TTE), Shell (SHEL), CNOOC, and CNPC.

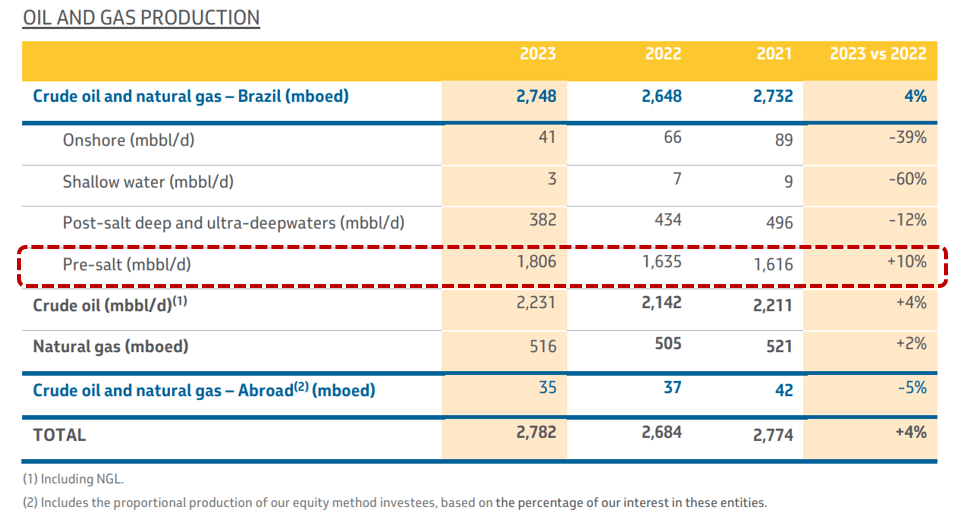

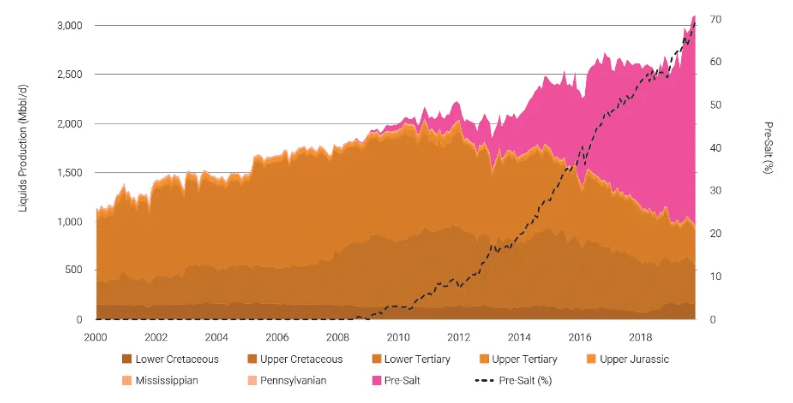

PBR discovered Brazil’s pre-salt fields in 2006. It achieved first oil in 2008 and began commercial production in 2010. That year, the fields produced a total of 41,000 boe/d. Their production has since increased to 1.81 million boe/d in 2023, equivalent to 80% of Brazil’s oil production and one-quarter of Latin America’s oil production. The table below illustrates the importance of pre-salt production in PBR’s E&P asset portfolio.

Source: PBR 2023 Annual Report Form 20-F. Red-dotted line added by author.

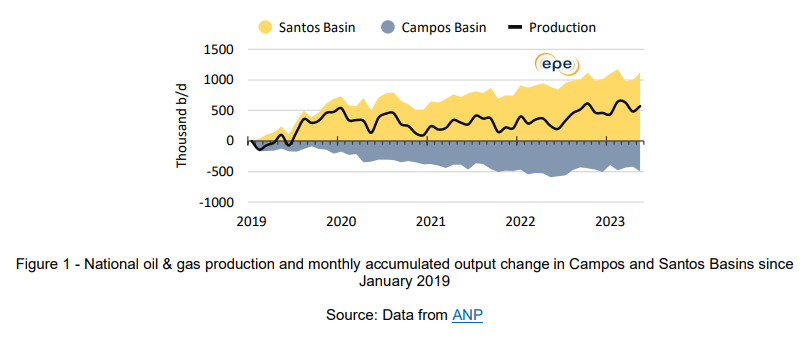

Of PBR’s pre-salt basins, the Campos is largely in decline. The basin has yielded dozens of discoveries since 1978, including four giant fields. PBR mitigates the basin’s declines through infill drilling mostly in its post-salt reservoirs.

Source: Empresa de Pesquisa Energetica Brazilian Oil & Gas Report 2022/2023, Dec. 21, 2023.

The Santos Basin, on the other hand, remains promising. PBR expects it to drive companywide production higher over at least the next five years. PBR’s pre-salt production is located in the “Pre-Salt Polygon” shown below.

Source: PBR 2023 Annual Report Form 20-F.

Most of PBR’s pre-salt production is located in the Santos Basin’s Tupi, Buzios, and Meri fields. The Tupi field was the first pre-salt oil field discovered in Brazil. It is the largest deepwater producing field in the world, with proved reserves of more than 8 billion barrels of oil equivalent and production capacity of one million boe/d. Buzios is a one million boe/d field that has been producing commercially since 2017. The Mero Field produces 180,000 boe/d and is expected to ramp to a maximum production of 600,000 boe/d.

Production Growth

PBR’s E&P economics are underpinned by the spectacular productivity of its wells. The company has 30 wells that produce more than 40,000 boe/d each and 15 to 20 that produce more than 50,000 boe/d each.

The productivity of PBR’s pre-salt wells and the prospect of a windfall from a new discovery have allowed the company to allocate vast sums toward exploration. For years, major pre-salt discoveries have resulted in consistently increasing production. The chart below shows the trend in place from 2000 to 2020 and the role of pre-salt production in driving it higher.

Source: Enverus.

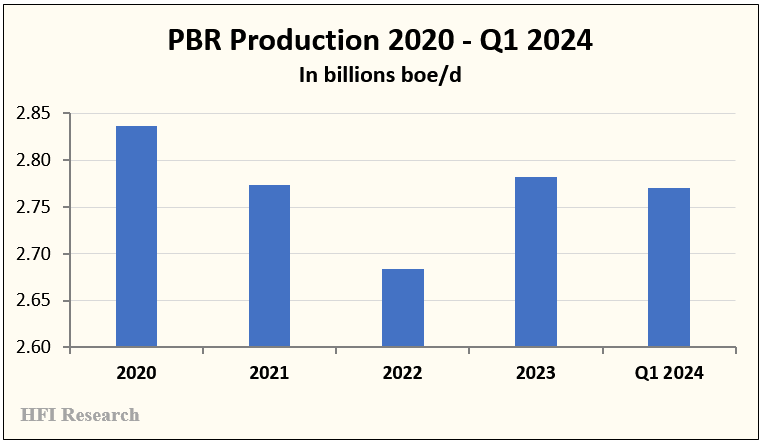

Since 2020, however, PBR’s production has flatlined. Production rates from 2020 to the first quarter is shown below.

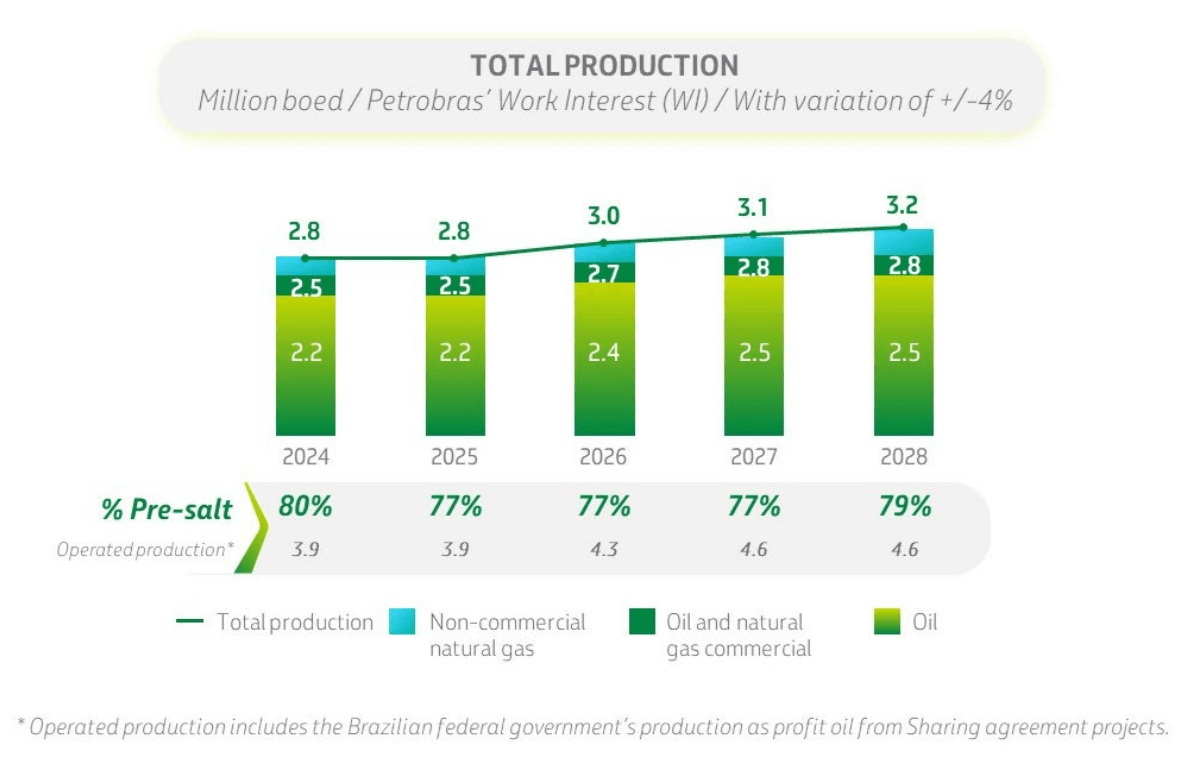

PBR is counting on its pre-salt assets to offset the decline of its older assets and drive growth higher over the coming years.

Every year, PBR puts forth a five-year plan to its investors that forecasts production and capex. However, each year’s plan changes significantly from the previous year’s plan, reducing the plans’ reliability as guideposts to PBR’s future activities. The latest five-year plan forecasts production growth from 2.8 billion boe/d in 2023 to 3.1 million boe/d. By 2028, the plan calls for 2.4 million of production to come from the pre-salt layer, representing 79% of total production.

Source: PBR 2023 Annual Report Form 20-F.

While PBR’s growth has been extraordinary, the company has routinely missed its own growth targets. We have no reason to doubt PBR’s ability to reach 3.1 million bpd, but its execution history vis-à-vis its production targets would suggest otherwise.

The Looming End of PBR’s Pre-Salt Era

Despite PBR’s plans for production growth, there are indications that its pre-salt production is topping out. Pre-salt crude oil production declines by approximately 10% per year, so without new discoveries, PBR’s total production could face challenges to growth at best and terminal decline at worst.

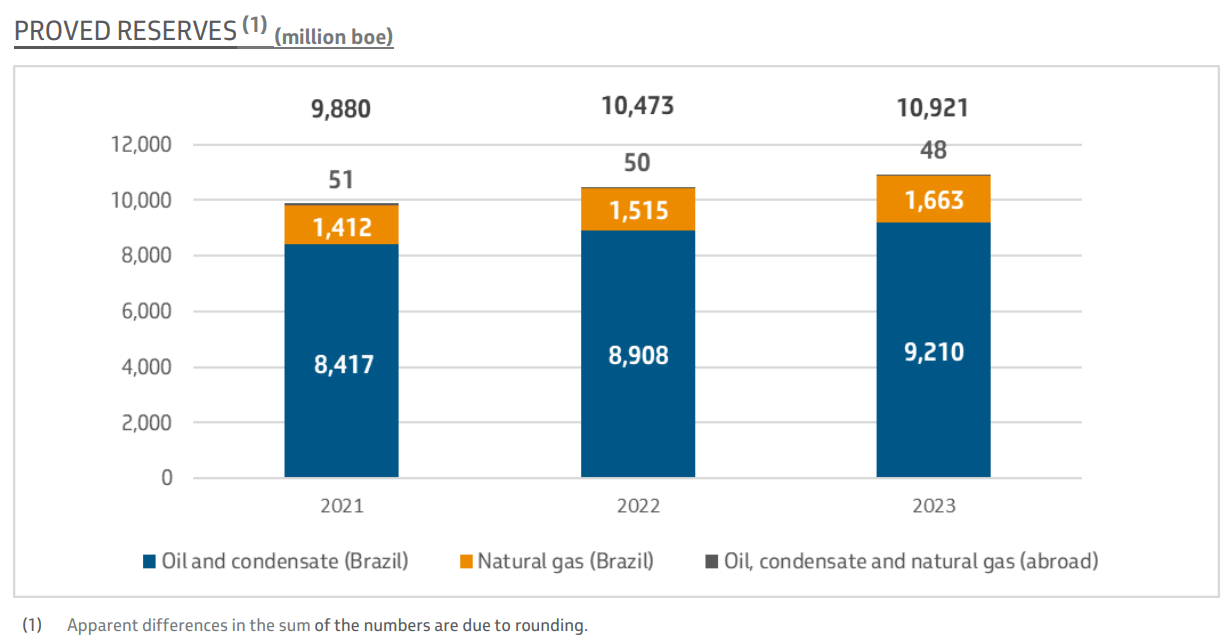

The prospect of declining pre-salt production is concerning for PBR shareholders. Over time, production at the current rate without new discoveries that boost reserves could result in declining reserve volumes.

PBR’s proved reserve life extends 11.5 years, enough to provide comfort to existing shareholders that intrinsic value is sufficient to cover their investment at the current stock price. But over the next few years, the company will have to extend its reserves further to mitigate the impact of depletion on reserve value, production volumes, and intrinsic value.

PBR has succeeded in replacing its produced reserves for decades. In 2023, it achieved a 150% reserve replacement ratio, which was attributable to the commercialization of the Raia Manta and Raia Pintada fields in the Campos Basin.

Source: Petrobras Form 2023 20-F.

Given the six-to-ten years of lead time and the significant financial investment necessary to develop a new pre-salt field, PBR has to find new large fields to extend its reserves. Recent exploration results have not been good despite efforts led by the world’s most successful exploration companies, from Shell to TotalEnergies to Exxon Mobil. Despite their efforts, the last major pre-salt discovery was made a decade ago.

While the company’s latest five-year plan, announced in November 2023, maintains its capex focus on pre-salt production, changes from the 2022 five-year plan are telling. The 2023 plan calls for an increase in capex but shows no commensurate increase in management’s production forecast out to 2027.

The 2023 plan forecasts $102 billion of capex over the next five years, boosting PBR’s forecasted capex over the 2022 plan by 31% and by 50% from the 2021 plan. E&P capex will comprise 72% of that amount, or $73.5 billion, up from $65 billion in the previous plan.

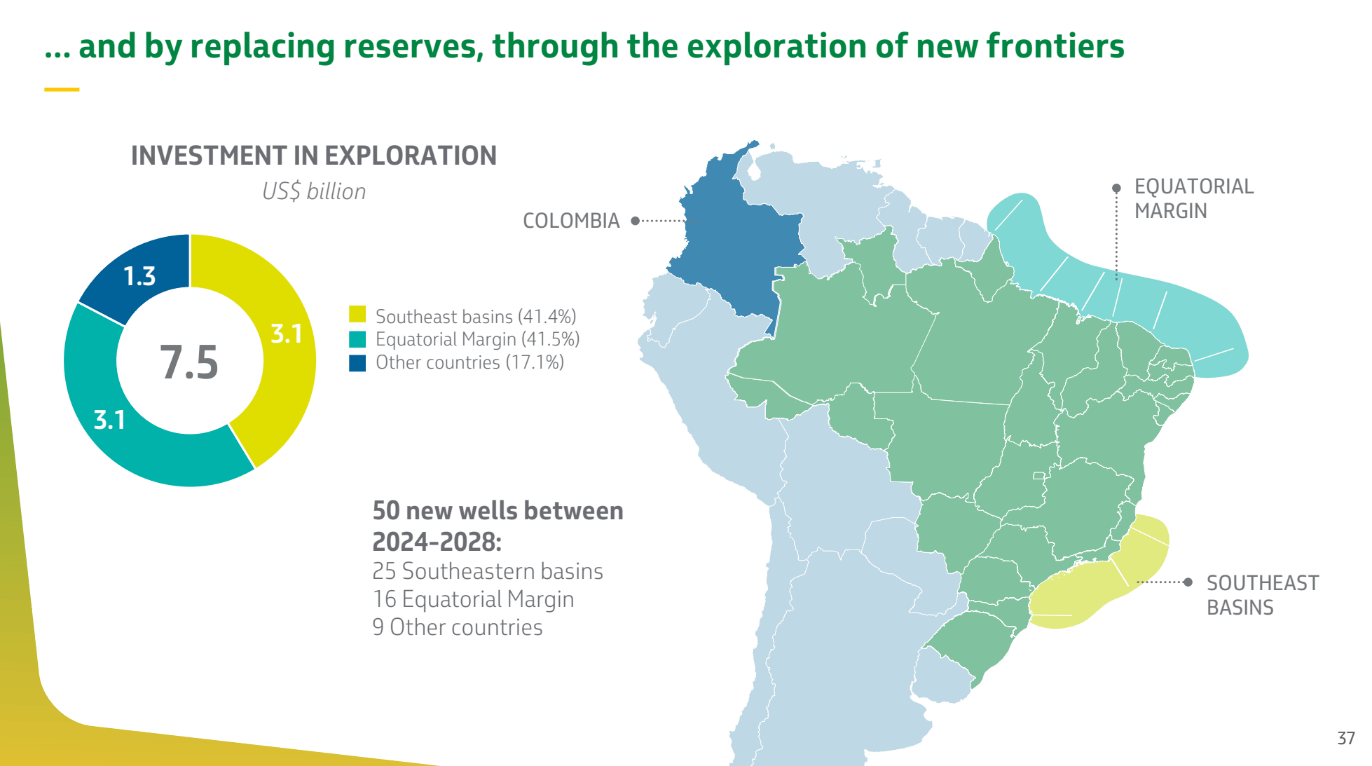

Of the $73.5 billion of capex allocated to E&P, approximately $66 billion will be spent on maintaining and growing existing plays, while $7.5 billion will be spent on exploration, up from the previous year’s estimate of $6.0 billion. A total of $3.1 billion will be allocated to the Equatorial Margin, $3.1 billion will be allocated to the Southeast Basins, where pre-salt production is located, and $1.3 billion will be allocated to exploration outside of Brazil.

Source: Petrobras 2024-2028 Strategic Plan Presentation, November 2023.

Recent drilling results in the pre-salt Southeast Basins called into question the prospects for PBR’s forecasted $3.1 billion of exploration spending in the region.

Consider that in 2023, PBR has drilled more dry wells, which it abandoned, than producing wells. Of the 17 wells drilled, only two were producing. Dry wells raise risks for shareholders by reducing a company’s capital efficiency and return capital employed while also raising the specter of accelerating production declines.

The disappointing exploration results caused PBR’s partners, including Shell, Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Repsol—and even PBR itself—to relinquish several exploration blocks.

Other factors further complicate future pre-salt exploration. Among them is the rising costs for the floating production storage and offloading vessels necessary to store and transport oil produced offshore in the pre-salt fields. Another is the international majors’ focus on U.S. shale instead of Brazil, as the nation’s offshore prospects are seen as dimming. Environmental concerns have also become an issue. TotalEnergies recently gave up on pursuing exploration after it faced insurmountable difficulties in obtaining drilling permits.

Even PBR executives have also spoken about the decline of pre-salt. No less than current CEO Magda Chambriard declared the pre-salt boom to be “over.” Private energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie also believes that the pre-salt development is nearing its end.

Energy market consultancy Rystad Energy is slightly more optimistic. It expects gross pre-salt production—including gross production from PBR’s partners—to increase from 3.5 million boe/d to approximately 4.0 million boe/d by 2030. It sees production entering terminal decline thereafter.

With pre-salt decline growing more likely, PBR’s diversification of its exploration activities to other areas appears to have a sound rationale. It is shifting its focus toward the Equatorial Margin and recently made an ultra-deepwater find in the region near Guyana. Nevertheless, we doubt these efforts will yield anything close to the bonanza provided by the pre-salt fields.

It may be a sign of urgency to find new discoveries that PBR even considered pursuing new projects in the Amazon River region. Its efforts even received backing from one of Lula’s aides. However, it reversed course after receiving stiff opposition from environmental groups.

Dual-Class Share Structure

Like most public companies domiciled in Brazil, PBR has a dual-class equity capital structure, with common shares that have economic participation and voting rights and preferred shares that have only economic participation. To compensate for the lack of voting rights, preferred shares are required to receive distributions equivalent to 25% of annual net income. Preferred shareholders get priority on all dividend payments and in a change of control situation. As long as more than 25% of annual net income is being distributed, common and preferred shareholders receive an equal amount of dividends.

PBR’s official dividend policy calls for it to distribute at least $4.0 billion in dividends in years when Brent averages more than $40 per barrel. If gross debt is $65 billion or less, PBR will distribute 45% of its free cash flow each quarter as a base dividend. Above those dividend distributions, PBR will pay extraordinary dividends.

PBR began to pay dividends greater than 25% of net income after deleveraging in 2021, after its long-term debt balance fell below $60 billion. In 2022 and 2023, it paid out most of its free cash flow in a combination of a base and special dividends.

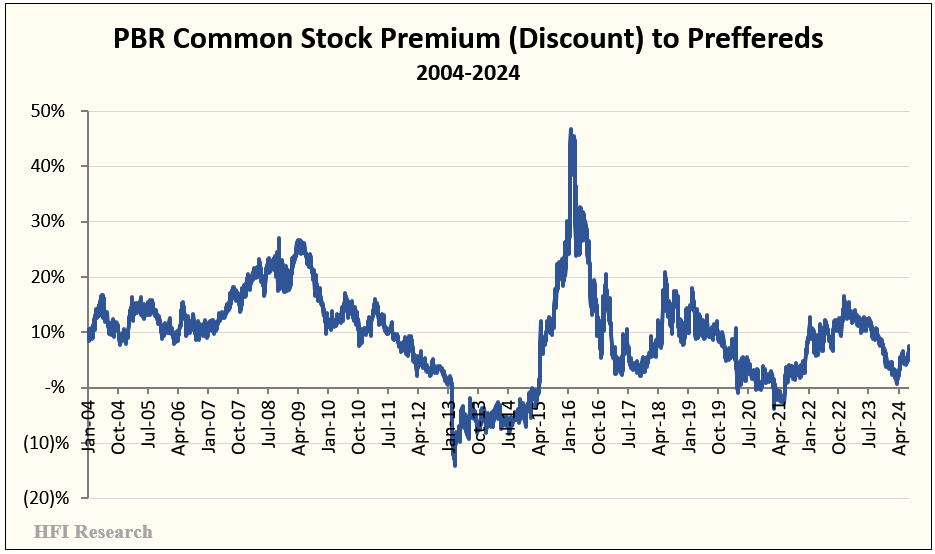

When PBR was financially distressed and common dividends were at risk in the 2015-2016 period, the preferreds traded at as much as a 40% premium to the common shares. Under normal circumstances, however, the preferreds trade at a discount, as they lack the voting feature.

The result of this pricing discrepancy is that the preferred shares trade at a higher dividend yield versus the common shares. For example, both shares received $2.07 in dividends over the past twelve months. The preferred shares, at $14.08, trade at a 14.7% yield, while the common shares, at $15.14, trade at a 13.7% yield.

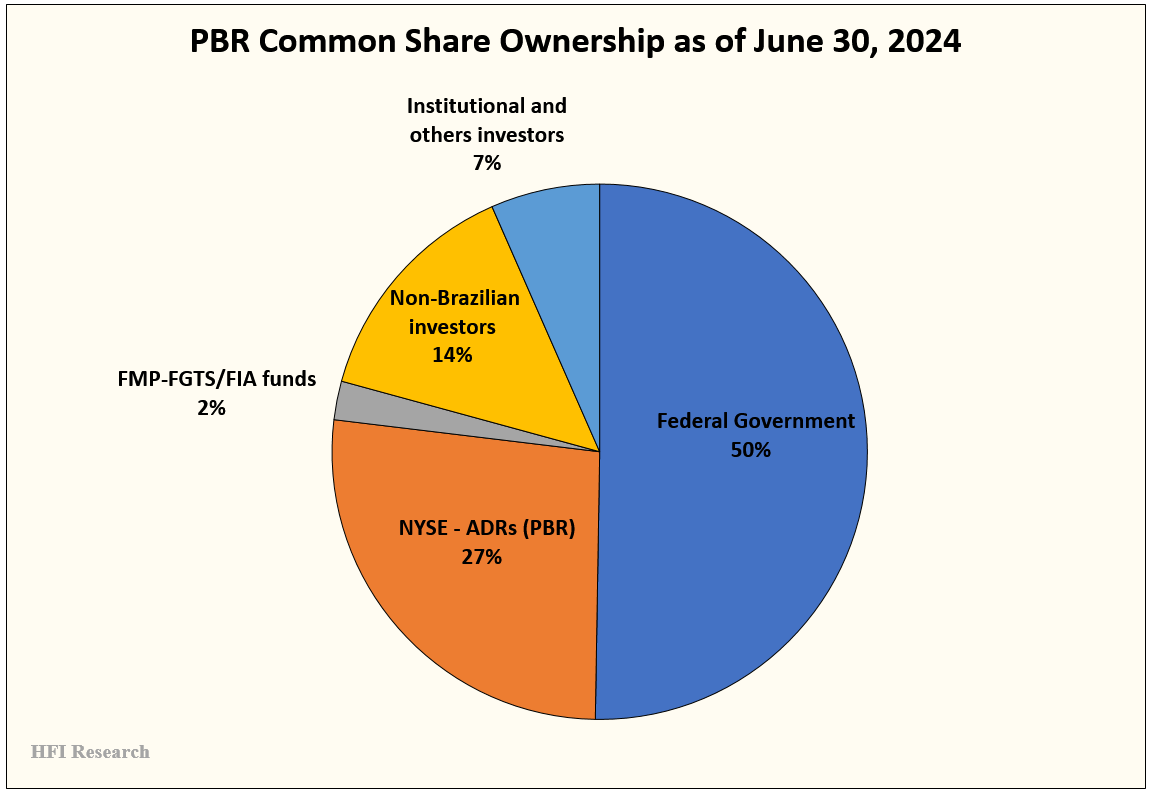

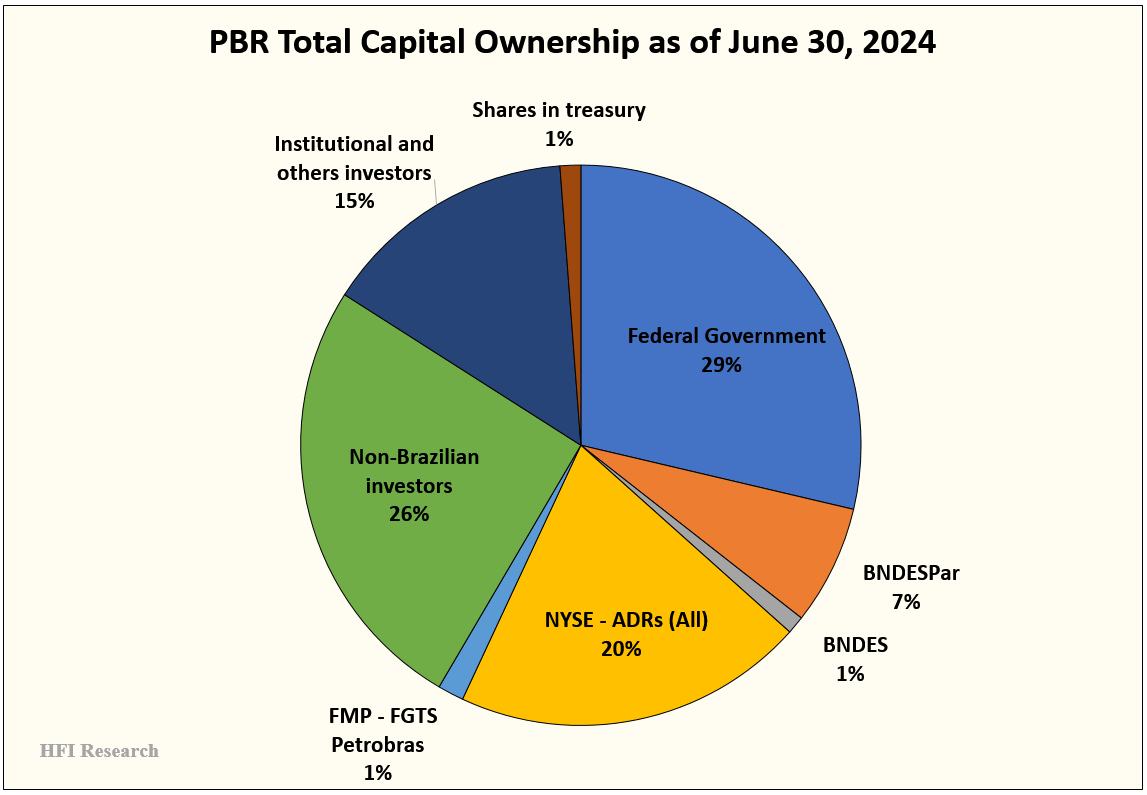

Brazil’s federal government maintains control through its 50.3% ownership of PBR’s common shares, as seen in the pie chart below.

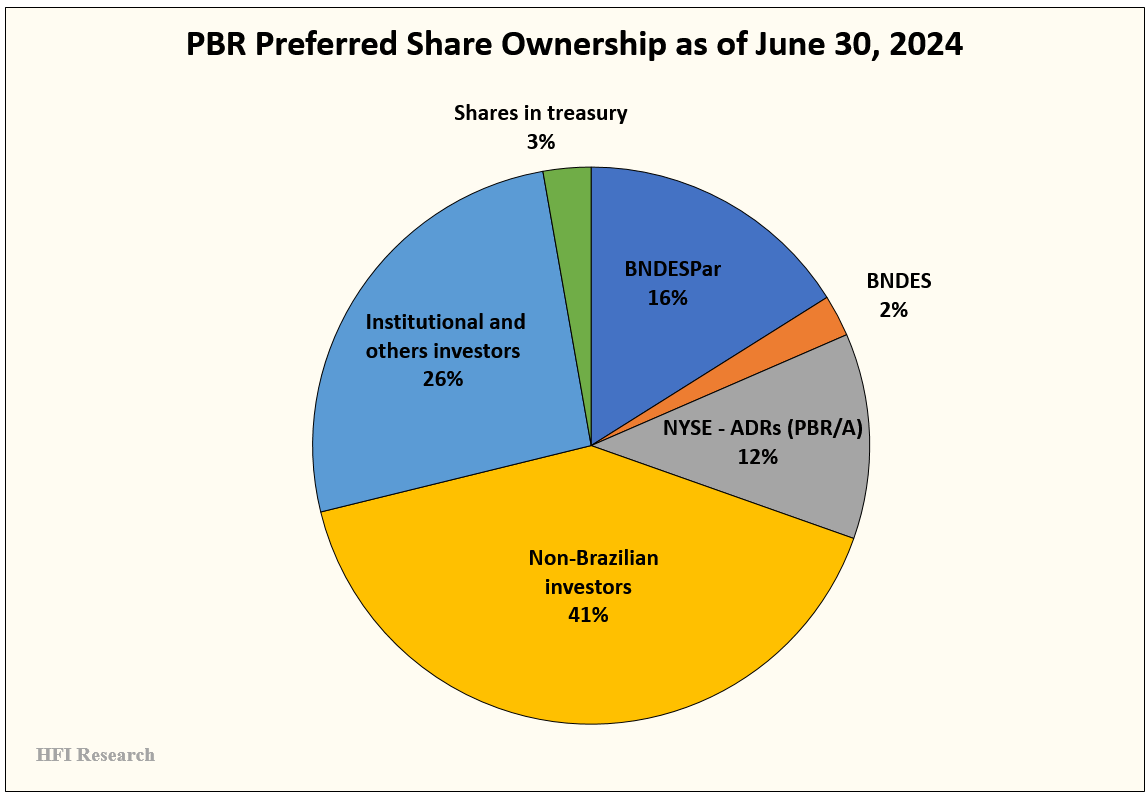

“BNDES” denotes the Brazilian Development Bank, and “BNDESPar” is BNDES Participacoes S.A., the investment arm of BNDES. These entities collectively own 18% of the preferred shares. Since both entities are owned by the Brazilian government, they essentially represent a government ownership interest in the preferred shares.

Altogether, the Brazilian government owns a 37% economic stake in PBR.

The different characteristics of the common and preferred shares make them more suitable for different types of investors. By law, the Brazilian government will maintain its 50%-plus stake in the company. PBR has shown no tendency to dilute either class. The common and preferred share counts have remained constant at 7.442 billion and 5.602 billion, respectively.

The common will benefit if PBR steps up share repurchases, as these are likely to reduce common shares outstanding. However, the preferred are more likely to retain value relative to the common in an inevitable cyclical downturn. They may even receive dividends when the common shares don’t.

Risks

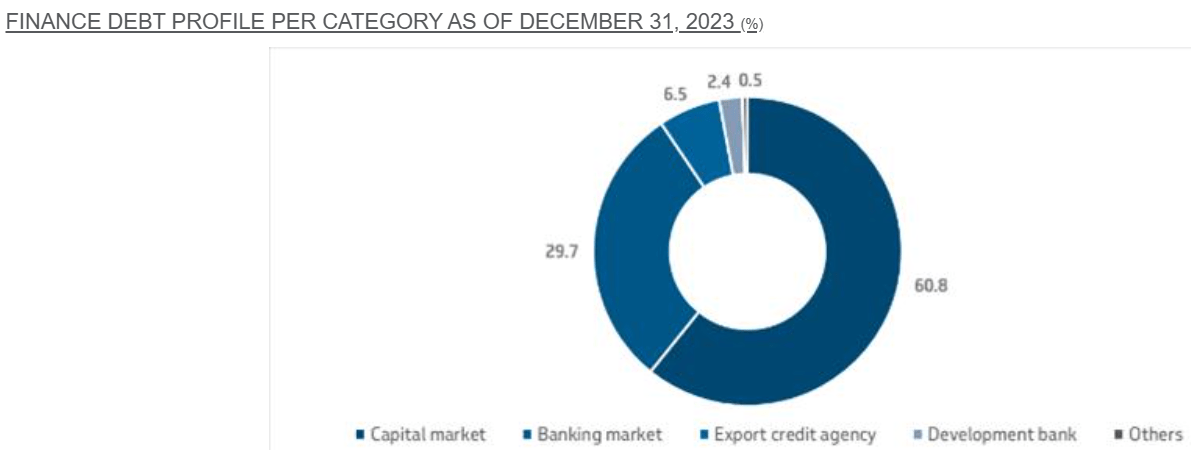

PBR’s financial risk is low. At the end of the first quarter, net debt stood at $43.6 billion, slightly more than one-time the $40 billion of cash flow the company generates at $80 per barrel Brent. Gross long-term debt of $61.8 billion has been on an uptrend that management has indicated it seeks to limit. Long-term debt stands 16% above the year-ago level, while net debt is up 14% since then. Even so, PBR is in the best position by far among major Latin American oil and gas producers.

The debt situation is a far cry from PBR’s former years, when price controls forced the company to take on increasing amounts of debt to fund capex and other expenditures. Today, net debt-to-EBITDA is currently less than one versus 5.2-times in 2015 after the Car Wash scandal, when PBR came close to a technical default. Its long-term debt peaked at $126.2 billion in 2015 but was reduced after $36.7 billion of divestments since 2016 and robust cash flow generation aimed at debt reduction in 2021 and 2022.

One financial risk was that 40% of the company’s debt was unhedged floating-rate debt. Rising interest rates could also increase debt service costs.

Source: PBR 2023 Annual Report Form 20-F

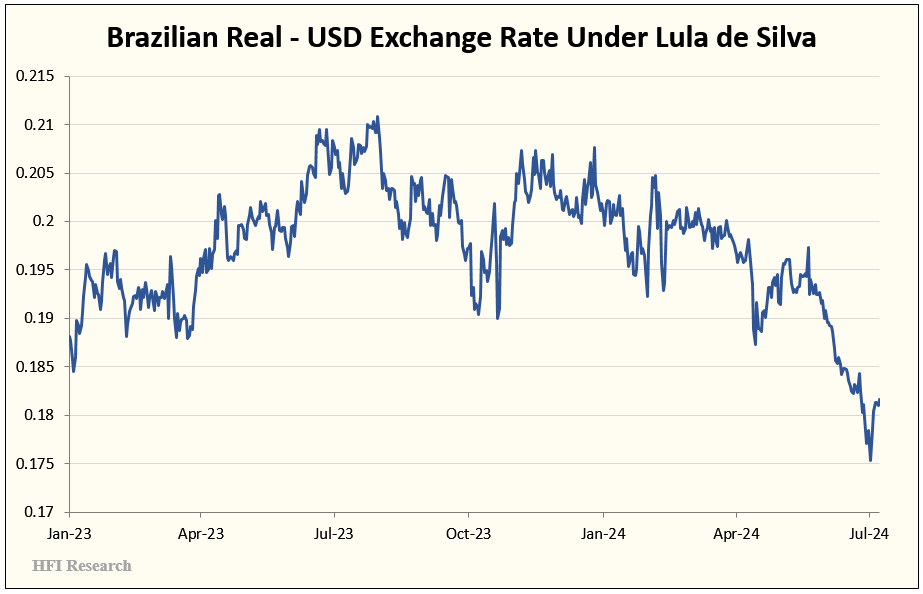

At the end of 2023, 80% of PBR’s gross long-term debt balance is denominated in currencies other than the Brazilian real, with 71% of long-term debt denominated in U.S. dollars as of the end of 2023. More than 70% of PBR’s oil is sold in Brazil. A significant depreciation of the real would increase PBR’s debt service costs. Lula’s latest oil export tax hike and interference in PBR pushed the Brazilian currency lower versus the U.S. dollar.

We do not view asset expropriation as a risk for PBR shareholders. We wouldn’t say the same for other Latin American national oil companies, such as Ecopetrol (EC) of Colombia. However, “windfall” profits taxes become a growing risk when oil and gas prices are high. We’d point out, however, that they’re also a risk in Europe and other regions viewed as less hostile toward capital than Latin America. The Irish and German governments levied windfall profits taxes on Vermillion Energy (VET:CA) in 2022 after its outsized earnings in response to high commodity prices. VET paid tax rates of 75% and 33% on windfall profits in those jurisdictions, respectively.

For Brazil, higher energy prices typically lead to higher inflation, which brings problems for the government. Persistent inflationary conditions may induce the Brazilian government to increase its take from PBR via increased royalties, increased income taxes, and/or increased special taxes. Higher inflation could also bring about refined-product price controls mandated by the government that force the company to sell its oil at a loss to domestic consumers, as it was forced to do in the years before 2013. Back then, reduced cash flow could cause the company to increase long-term debt to fund its capex. Today, a higher debt balance would lower PBR’s credit rating, increase its funding costs, and ultimately endanger dividends for the common shares.

PBR’s financial problems could be compounded if the Brazilian government forces the company to keep its payroll bloated so as not to exacerbate layoffs in a downturn. And if layoffs were to occur, large-scale strikes could reduce PBR’s earnings and damage relationships between management, labor, the government, and private investors.

Operational risks include the massive clean-up costs that would likely arise in the event of a blowout of an offshore well.

Despite the tons of ink spilled on PBR’s political risk and its consequences to PBR’s operations and finances, we view the company’s greatest risk to be long-term asset depletion. Whereas the market may be comfortable assuming PBR can indefinitely replace more than 100% of its annual production, we don’t expect that to remain the case. The next five years will be telling.

If it turns out that PBR’s reserve replacement ratio begins to fall, signaling the advent of long-term production decline, will the Brazilian government, as the controlling shareholder, become more activist in company affairs? Does it view the imminent risks as sufficiently severe to tilt the scales in its favor by penalizing outside private shareholders? We don’t know the answers to these questions, but as typically happens when an economic pie begins to shrink, conflict becomes more likely. We wouldn’t want to be in a position where we receive the short end of the stock.

Valuation & Commodity Price Sensitivity

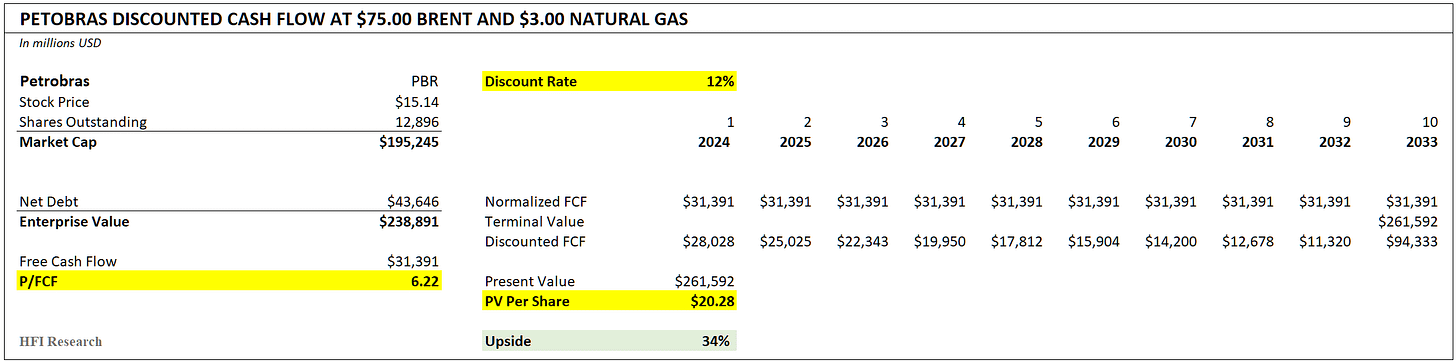

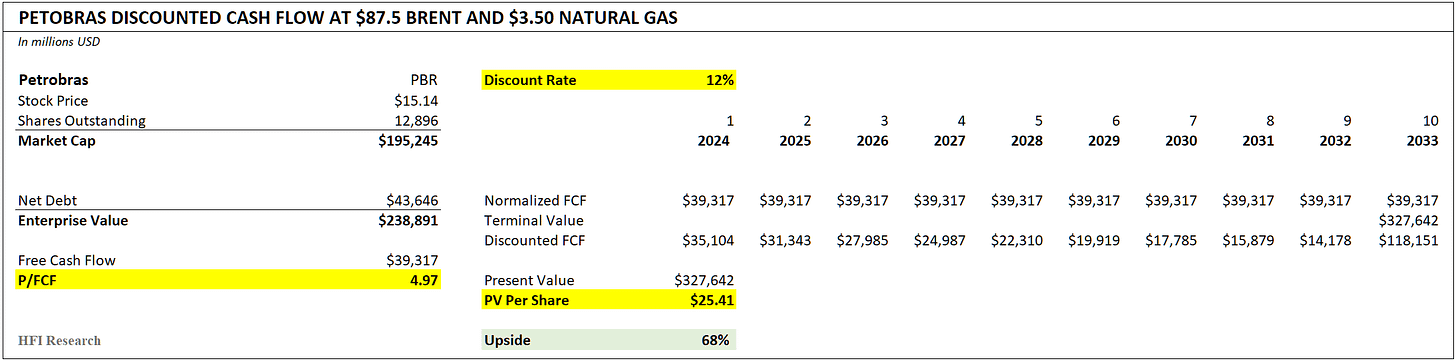

We value PBR shares in the range of $20 to $25 without considering the risk to future cash flows.

Our discounted cash flow valuations estimate value per share at $75 per barrel Brent/$3.00 per mcf natural gas and $87.50 per barrel Brent/$3.50 per mcf natural gas, both using a 12% discount rate. We consider this to be a conservative long-term price range, and we use these prices as lower and upper bounds on our valuation range. Our valuation represents PBR’s total equity value per share, including all common and preferred shares outstanding.

The lower bound of the value range implies 34% upside from the current common stock price of $15.14.

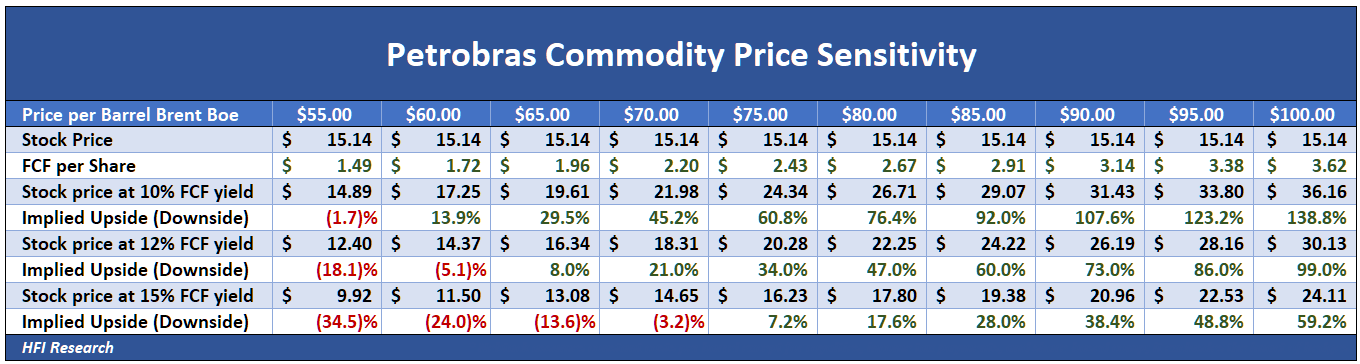

At $80 per barrel Brent, we estimate PBR would have dividend capacity of $2.67 per share. If the company paid out all its free cash flow as dividends at that oil price, its dividend yield would be 17.6%. However, PBR is likely to retain cash flow for debt reduction and other purposes, so its actual dividend yield would likely remain in the 12% to 14% range, absent political interference.

PBR’s free cash flow breaks even at $45 per barrel Brent, assuming budgeted capex. If PBR operated in maintenance mode, its breakeven per barrel would fall below $30 Brent.

PBR has significant cash flow torque to higher commodity prices, particularly with the share price so depressed versus intrinsic value. At $100 per barrel Brent, the stock would trade at $30.13 per share, represeting nearly 100% upside. This valuation would come about assuming the shares traded at a 12% free cash flow yield and before consideration of risk to future cash flow.

Instead of changing our valuation to reflect the possibility that future cash flow is impaired by an adverse event, we would rather simply demand a larger margin of safety in our purchase price. Today’s $15 per share is verging on “not big enough” relative to the $20 per share lower bound of our valuation range. We would prefer to buy PBR shares in the $12.00-to-$13.00 range. At that price—assuming we continue to expect higher oil and gas prices over the long term—we would expect either price appreciation or a high forward dividend yield to offset much of the long-term financial risk in the share price. If history is any guide, perceived financial risk is likely to be greater than actual financial risk, so we could be eager buyers of the shares for long-term holding.

Our favored way to buy PBR stock would be to wait for some sort of fear to send the shares lower. It could be the fear of dividend restrictions or managerial turmoil. Or it could be a cyclical downturn that imperils the common dividend. Under such circumstances, we would wait for the spread between the common and preferred to narrow. When it does, we would consider buying the common shares. At that point, they would trade at a similar dividend yield—assuming the common dividend was safe—and they would offer more upside relative to the preferreds.

More conservative investors should stick to the preferreds. Their dividend will always be safer than the common shares and they are more likely to retain their value in a cyclical downturn.

Conclusion

The headlines surrounding PBR imply greater economic risk than actually exists in the shares. We expect the shares to continue to be as volatile as Brazil’s political atmosphere.

We would refrain from buying until fear creeps back into the share price, at which point we would be comfortable owning a 5% position in the shares, and perhaps slightly more if the price was low enough and total return prospects were sufficiently attractive.

PBR shares at their current price are an attractive alternative for income investors who seek E&P exposure. Unless oil prices fall below $70 per barrel, we expect their yield to remain above 10% inclusive of the 15% withholding tax that most U.S. citizens pay on Brazilian stocks.

PBR presents an attractive economic package. Investors should patiently wait for the price that suits their investment needs and risk tolerance and hold for the long term.

Analyst’s Disclosure: Jon Costello has a beneficial long position in the shares of VET either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives.