President Trump launched a successful operation in Venezuela and captured the Venezuelan President, Nicolás Maduro. We won’t go into the geopolitical reasons for the US actions or any other geopolitical factors; we will leave that to experts like Dr. Anas Alhajji.

Instead, we will focus this piece on these impacts:

Oil price impact.

Dynamics of sanctioned barrels and unsanctioned barrels, and how that impacts supply & demand.

Implications on long-term global oil market fundamentals.

Equities that could benefit.

Implications on Oil Price

In normal market environments, a regime change in an oil-producing country would be immediately bullish for the oil market as traders assume 100% disruptions to crude export flows.

In this case, oil exports out of Venezuela do not constitute “normal”.

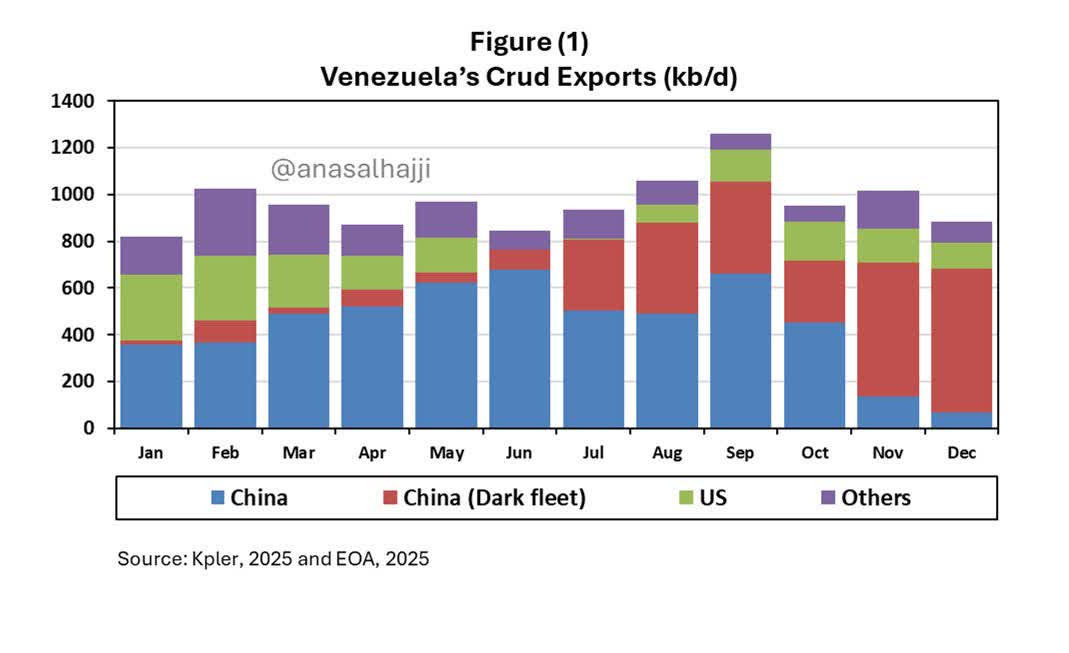

Venezuela only exports ~800k b/d, with almost the entirety of the exports going to China via dark fleets.

Source: Dr. Anas Alhajji

The reason why this is so important to understand is that China is the “only buyer” of “sanctioned” barrels. When you think of sanctioned barrels, these are oil exports from Russia, Iran, and Venezuela. Sanctioned barrels operate under a different physical pricing dynamic than unsanctioned barrels.

In this particular case, given that China is the only buyer of sanctioned barrels, it enjoys a healthy discount to the spot price. China can exert its enormous buying power and demand large discounts for the crude. This, indirectly, hurts unsanctioned barrels as it reduces demand from China on outside barrels, and thus, pressures oil prices.

Now that Maduro is out and China will no longer be able to take advantage of “cheap” crude from Venezuela, this ~800k b/d will open up to the unsanctioned segment of the oil market. In other words, oil traders will assume that Venezuelan crude exports will be made available to the rest of the world, and they will compete like-for-like with other heavy oil exporters, such as Mexico and Canada.

Keep in mind that the dynamics we are describing here assume no meaningful disruption to Venezuela’s crude exports.

All things equal, the sudden availability of Venezuelan crude to the unsanctioned segment of the oil market is net bearish. From a fundamental standpoint, the unsanctioned segment of the oil market would desire the heavy crude that Venezuela exports, especially to US refineries.

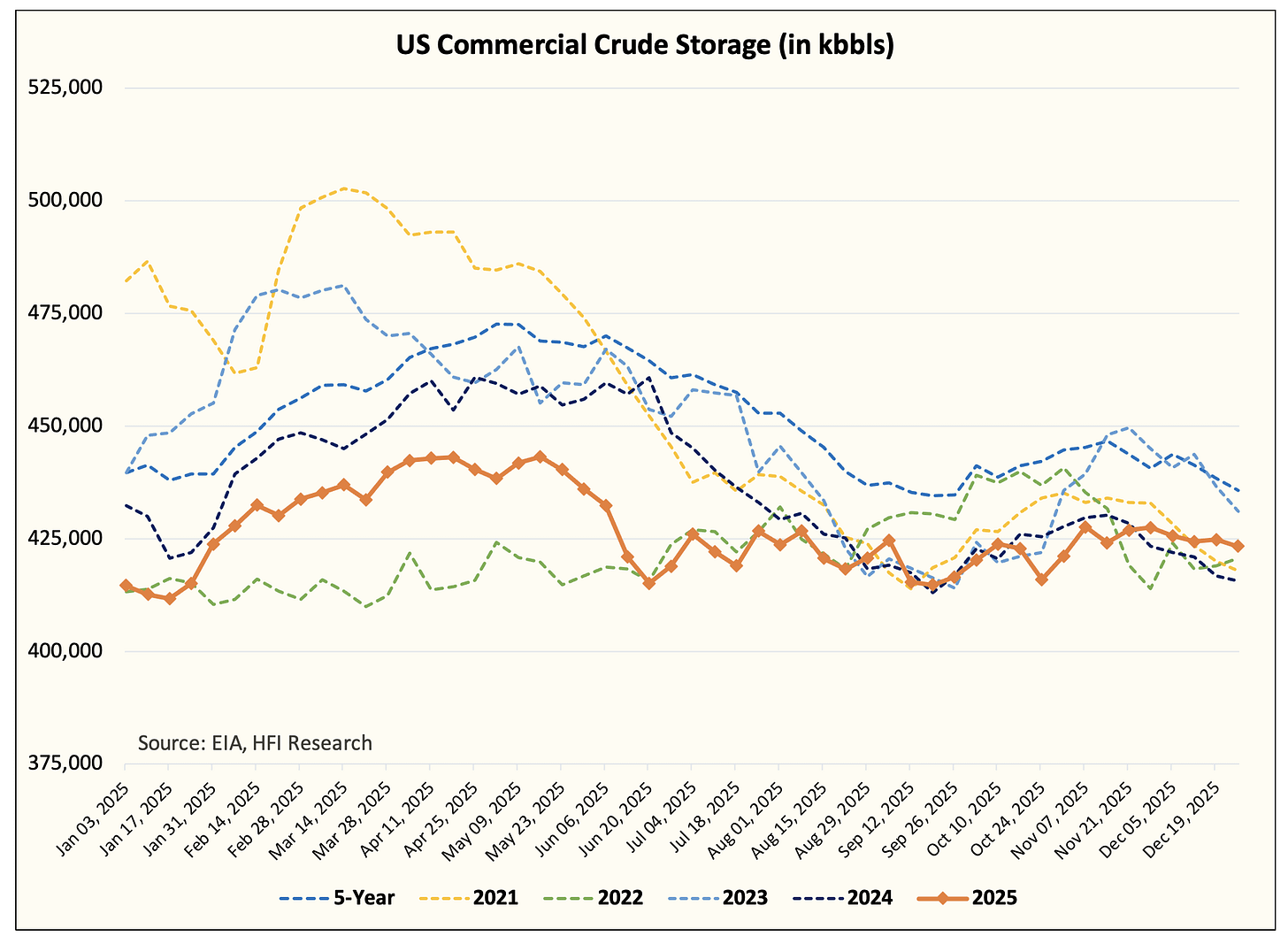

US commercial crude storage is already near multi-year lows, and with the recent drop in refinery margins, the availability of heavy crude will be a net positive for US Gulf Coast refineries.

As a result, our view on the oil price impact in the near-term is that it’s a net-negative. We see a small downward move in price ($2/bbl).

Supply & Demand (2026)

The unsanctioned segment of the oil market will need the crude available from Venezuela. China, which has enjoyed the discretion of being the sole buyer of Venezuelan crude for a very long time, will need to start stockpiling other sources of crude if it intends to fill up the SPR this year.

The increased buying from other sources may result in a more medium-term bullish impact on oil. While the market’s initial reaction is to assume that it’s bearish and the unsanctioned segment of the oil market will now have to compete with Venezuelan crude oil, the eventual increased buying from China will help prop prices back higher.

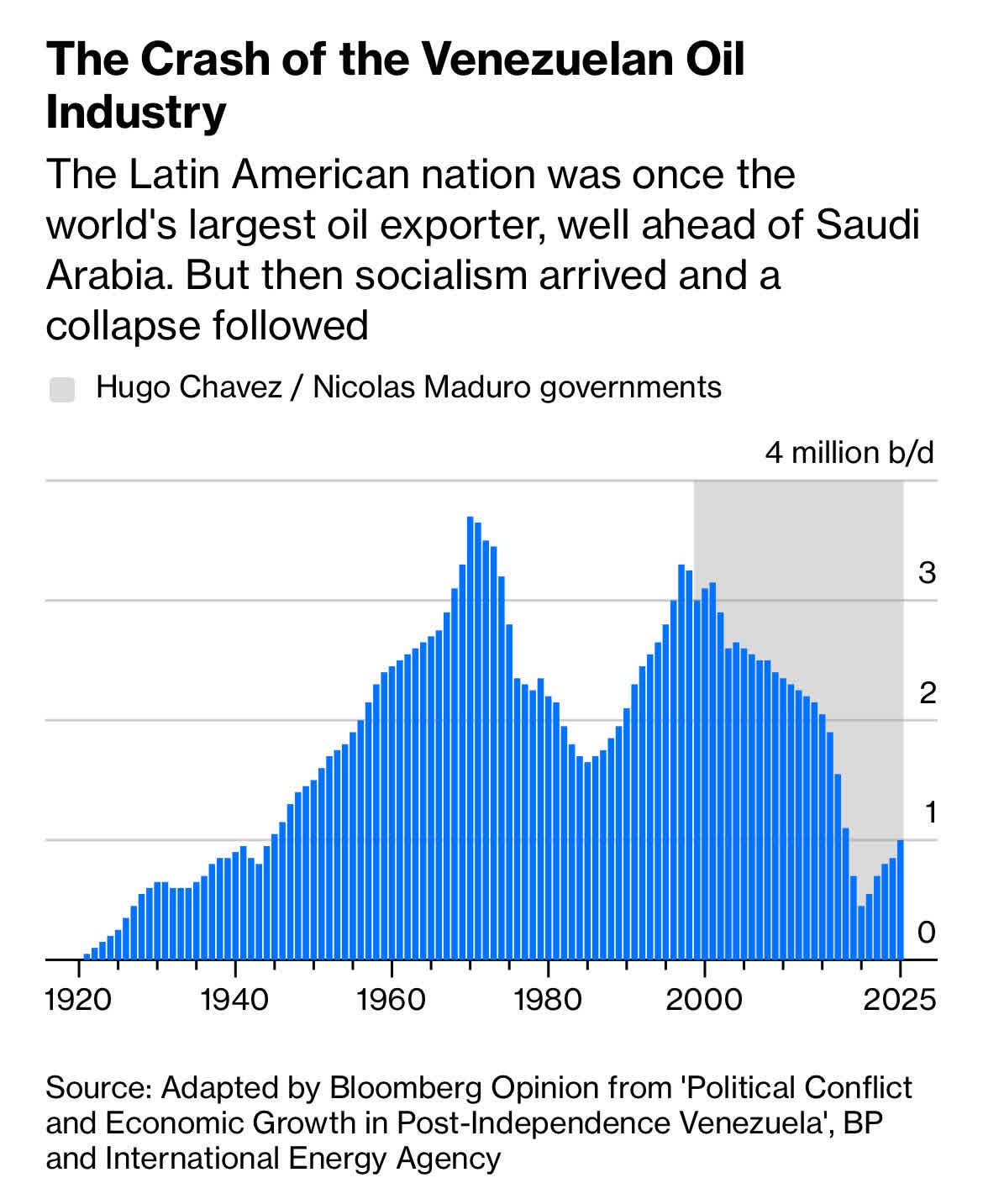

From a supply & demand standpoint, Venezuela’s oil production of ~1 million b/d will not see any meaningful increase anytime soon. Oil infrastructure in Venezuela is so deteriorated to the point that any meaningful increase in production will take billions and years of capex.

We estimate that if US oil majors express interest and commit to investing in Venezuela, it would take 2-3 years to increase production by ~500k b/d. There is still a lot of uncertainty on the ground, and no one knows what the transition would look like or whether there’s chaos during the transition. So please take that 2-3 years with a grain of salt.

Once there’s more clarity on the political transition and assuming no more chaos, and only if oil majors in the US commit, then the time clock begins. Venezuela has a lot of low hanging fruits that will see production bump up quickly, but to have a sizable and sustainable ramp, that would take 5+ years (at minimum).

For our global oil supply & demand model, I think it’s safe to assume that Venezuela’s oil production will remain around ~1 million b/d for this year. Even if we see a sizable commitment from the majors, oil production would not meaningfully increase this year.

So if you are wondering how this Venezuela news impacts global supply & demand this year, the answer is: nothing.

Long-Term Supply & Demand Model

There is still a lot of uncertainty as to what the “new” Venezuela would look like, but if we assume a US-friendly regime and one that’s pro-oil, then there’s a plausible scenario where Venezuela could reach ~2 million b/d by 2032-2033.

The technical background will be complicated to meaningfully increase production. First, the oil infrastructure in Venezuela was in terminal decline since the early 2000s.

From industry experts we’ve spoken to in the past, Venezuela’s oil sector would require a complete overhaul of all the equipment to sustain production anywhere near ~2 million b/d. You might temporarily get production higher, but to sustain that level, you would need billions of capex.

Oil majors will not make such a commitment and investment unless they are certain that 1) the regime change is safe and 2) there are legal processes in place that can support legal ownership.

Even if all the frameworks are in place, it would take time before they can convince conservative boards to aggressively pursue the Venezuela option. The only mechanism that we think could expedite this is if the US government throws its weight behind guaranteeing the contracts. Outside of that, oil majors will wait.

In our view, the earliest Venezuela will impact global oil balances won’t be until 2028 to 2029, and for it to increase by ~1 million b/d, we would have to wait until 2031 to 2032.

Because of this dynamic, the Venezuela situation does not meaningfully change the future global oil market balance.

Equities

There are very limited direct beneficiaries of this. Sanctions imposed on Venezuela led many oil companies to avoid Venezuela altogether. In this case, Chevron is the only oil major still operating in Venezuela thanks to a special license granted by the US government.

From an operational standpoint, because of Chevron’s continued involvement there, it would be the first oil major to truly understand the political transition. It would also have a board that would be supportive of an aggressive move in Venezuela. It would not surprise me if Venezuela could, eventually, add ~350-400k b/d for Chevron. This is a clear positive for Chevron.

Another equity name that would benefit is New Stratus Energy (NSE.V). NSE previously had ownership in a Venezuelan joint venture with Goldpillar. The company announced at the end of 2024 to exit following Trump’s presidential victory. In fear of sanction risks and increased geopolitical turmoil, NSE took a loss, but kept an arrangement in place to buy the stake back in the event of any meaningful political change. We reached out to the company, and the President informed us that it can buy it back for $1.

Background of the JV: The joint venture asset produced ~1,300 boe/d (at the time of the exit) with a historical capacity of ~60,000 boe/d. Here’s the press release when it was first announced.

Other oil companies that would benefit from this include:

Schlumberger (SLB), Halliburton (HAL), Weatherford (WFRD), Baker Hughes (BKR): To increase Venezuela’s production capacity, oil majors will need to spend billions on capex and service providers. Oilfield servicing stocks would benefit.

Exxon and ConocoPhillips: These two oil majors had history with Venezuela in the past and are very familiar with the assets. While the board will be highly skeptical due to past disputes, if the geopolitical climate is more certain, we see both oil majors re-entering the fold.

Conclusion

In summary, the initial market reaction might be bearish as oil traders will assume that the sanctioned barrels will now compete with the unsanctioned barrels. But in the medium-term, China will look to replace the lost crude from Venezuela, so the buying (in the unsanctioned segment of the oil market) will be a net-positive for oil prices. And in the long-run, the impact of the regime change is negligible on global oil market balances. Venezuela is already producing ~1 million b/d, and production won’t increase to 2 million b/d until 6-7 years from today.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of NSE:CA either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives.